Epidemiologic research supports the provocative hypothesis.

Past studies have suggested that several different infectious agents, including HHV-6, might be a trigger in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and other dementias, although a role for HHV-6 remains controversial (Komaroff 2020). Moreover, some investigators doubt that any infectious agent is likely to be involved in the pathogenesis of AD.

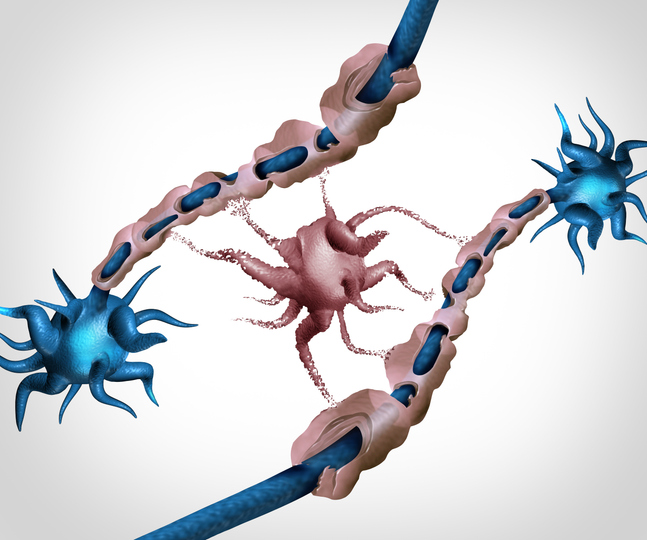

However, the theory that infection may be one trigger of the pathogenesis of AD and other dementias has only gained strength in recent years. The pathogenesis of AD clearly involves the accumulation of two molecules—amyloid-ß (which forms characteristic plaques) and tau (which forms characteristic tangles)— and is augmented by the inheritance of two alleles of apolipoprotein E4 (APOE4) as well as by neuroinflammation.

This widely-accepted hypothesis begs at least two questions: what triggers the neuroinflammation, and what causes accumulation of amyloid-ß and tau? In recent years, a growing body of evidence argues that—at least in some people—the answer to both questions may be infection.

It’s easy to see how infection might be one cause of neuroinflammation. Not only are multiple viral and bacterial agents capable of infecting the brain—surely including the herpesviruses—but infection outside of the brain can send humoral and neural signals to the brain that activate neuroinflammation.

While some investigators still search for a single, novel infectious agent that might be the cause of AD, the best evidence against the existence of an “Alzheimer’s germ” is that multiple infectious agents already have been incriminated as potential triggers of some cases of AD.

A recent publication in Nature Aging supports the hypothesis that multiple different types of infection can be one trigger of AD and other causes of dementia. The study used data from an integrated, nation-wide health information system in New Zealand in which over 1.7 million adults under age 60 who were born between 1929 and 1968 were then followed from 1989 to 2019.

Those individuals who had been hospitalized for any type of infection were compared to those who had not been hospitalized for an infection, with regard to a subsequent diagnosis of dementia. The former group had nearly a 3-fold higher risk of developing dementia (hazard ratio 2.93), after multivariable statistical adjustment for other factors (other physical and mental diseases, lifestyle, socioeconomic status) known to influence the risk of dementia. Strongly increased risk was found for viral, bacterial, parasitic and other infections.

While it is obvious that infection can stimulate inflammation, it is less widely known that infection also can stimulate the production of both amyloid-ß and tau. Amyloid-ß has been evolutionarily preserved throughout the animal kingdom: therefore, it likely has a beneficial function. Indeed, it has been shown that amyloid-ß appears to be an antimicrobial peptide, secreted in response to infection, and able to aid the eradication of both viruses and bacteria (Eimer 2018). And there is growing evidence that increased expression of amyloid-ß then leads to increased expression of tau.

This study did not report the relative frequency or importance of herpesvirus infections, specifically, among the viral infections found to increase the risk of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia. Nevertheless, its findings support the hypothesis that chronic latent infection of the brain by neurotropic viruses capable of reactivation and thereby provoking a neuroinflammatory response, could be one trigger of neurodegeneration.

Read the full article: Richmond-Rakerd 2024