Viral infections, especially enterovirus infections such as coxsackie B3, have long been suspected of triggering the autoimmune response that leads to type 1 diabetes (Principi 2017). To determine whether HHV-6 could be involved in the development of the disease, a team of Swedish researchers tested for HHV-6A/B in the pancreatic tissue of 8 type 1 diabetes patients and 12 non-diabetic deceased donors. They performed quantitative PCR as well as immunohistochemistry to look for proteins produced by active HHV-6 and reverse transcriptase PCR to look for messenger RNA.

HHV-6B DNA was found in two thirds of patients and controls, while HHV-6A was not found. HHV-6B late protein (suggesting previous active infection) was found in all type 1 diabetes patients and controls. By RT-PCR, no samples were positive for HHV-6B mRNA, conflicting with the results obtained via immunohistochemistry (IHC). If the virus was indeed active, as suggested by IHC, the level of transcription was likely below the level of detection.

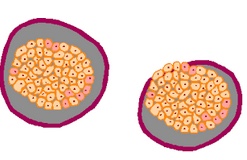

Using PCR, the investigators found HHV-6 DNA in the pancreatic tissue of 1 of 2 donors who had died of acute-onset type 1 diabetes, 4/6 donors with longstanding type 1 diabetes, and 9 of 12 nondiabetic individuals. For several donors, HHV-6B viral load was higher in isolated islets than in matched exocrine tissue. RT-PCR specific for the U100 transcript, which encodes a late envelope glycoprotein, was negative across the board. In contrast, scattered positivity for the p101k HHV-6B late antigen, encoded by U11, was detected in all samples, including those that had tested negative for HHV-6 DNA. On the other hand, HHV-6 positivity/negativity of a donor’s frozen tissue, which was used for the initial PCR, matched the PCR status of his/her FFPE tissue, which was used for IHC, indicating that the IHC positivity did not result from regional differences within the pancreas nor the use of FFPE tissue.

The authors explain that if the viral infection is characterized by periods of reactivation in scattered pancreatic regions, detection and analysis would be difficult, requiring large tissue samples harvested at just the right times. They add that determining the specificity of the memory T cells surrounding the islets in individuals with type 1 diabetes might be useful, as the presence of HHV-6-specific T cells would point to a role for HHV-6 in the disease.

This data differs from the results reported at the 10th International Conference on HHV-6 & 7 in July 2017. There, an investigator from the La Jolla Institute for Allergy and Immunology reported finding high levels of HHV-6B proteins in islet cells of patients with type 1 diabetes, but not in autoantibody positive donors or non-diabetic controls. They used confocal microscopy and high resolution laser scanning to examine the tissues and found higher intensity in the islet cells of type 1 diabetes patients compared to controls.

Since latent HHV-6 can be found in many healthy control tissue samples, quantitative measurements are important for determining the contribution, if any, by HHV-6 to the disease process.

Autoimmune sequelae are common in survivors of drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS), which is characterized by strong reactivation of HHV-6. Two studies found that 3.4-6.7% of DRESS patients developed type 1 diabetes after resolution of the syndrome (Chiou 2008, Kano 2015). Continued investigation into the contribution of the virus to immune dysregulation may reveal a more nuanced relationship between HHV-6 and autoimmunity.

Read the full paper here: Ericsson 2017.