Systematic review and meta-analysis confirm an association, but not a causal link, between HHV-6 and CFS.

Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS)—previously called just chronic fatigue syndrome—affects as many as 2.5 million people in the U.S. It often follows an apparent (but typically undocumented) infectious-like illness. ME/CFS is similar to post-infectious illnesses that can follow mononucleosis, Lyme disease, COVID-19 and other well-documented acute infections.

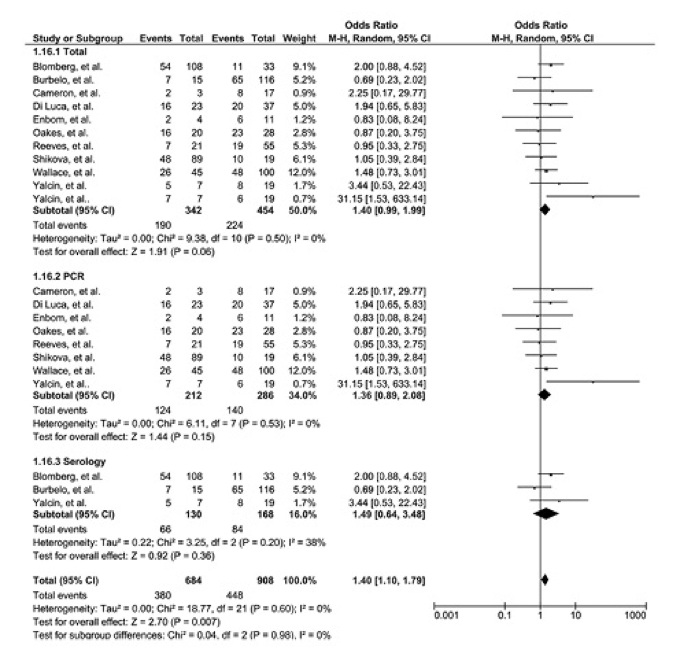

Because some reports have linked HHV-6 to ME/CFS, Mozhgani et al from various biomedical institutions in Iran performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of the role of HHV-6 in CFS. The investigators identified 17 studies including a total of 1,720 patients. Using well-established techniques, the investigators found no evidence of publication bias and acceptable levels of homogeneity across the studies, indicating that calculations from the pooled data of these 17 studies were likely to provide reliable information. The studies used both serological methods (antibody levels) and nucleic acid methods (PCR) for detecting HHV-6.

The pooled odds ratio for development of CFS was 3.50 (95% CI, 1.80 - 6.82). When studies that used PCR alone, or that used serology alone, were pooled, the significant association held, although it was higher for serologic studies: PCR OR : 2.43 [95% CI: 1.28–4.61]; Serology OR: 5.89 [95% CI: 1.48–23.45].

Figure 1: Forest plot of 11 studies that resulted in homogeneity.

Unfortunately, the authors do not provide much detail about the criteria used for determining a “positive” result for HHV-6, based on either PCR or serological evidence. Since the vast majority of humans remain permanently infected with HHV-6 from a very early age, almost everyone is seropositive for the viruses. So, studies using serologic data to link the viruses to ME/CFS would have to rely on serologic evidence of reactivated infection, or much higher antibody levels in cases than controls.

Similarly, with nucleic acid studies, the authors do not make clear whether the studies sought to detect HHV-6 nucleic acid in PBMCs, serum or plasma, or in biosamples other than blood, like cerebrospinal fluid.

Another problem is that most primary infections with HHV-6 occur at a young age, yet most cases of ME/CFS begin in people aged 20-50. Thus, primary infection with HHV-6A/B could not be the explanation of most cases of ME/CFS. Instead, as the authors allude to, reactivation of HHV-6 (either in the brain or elsewhere in the body) is a more likely explanation of any possible link with ME/CFS. Unfortunately, few of the studies included in this systematic review and meta-analysis were designed to carefully distinguish reactivated from latent infection, and none examined infection in the brain.

Finally, even if reactivation of HHV-6 is more frequent in people with ME/CFS, this could be an epiphenomenon reflecting underlying immune dysfunction in ME/CFS. It would not prove that reactivation of HHV-6 contributes to the pathogenesis of ME/CFS. Thus, more and different studies will be required to determine if HHV-6A/B contributes to the pathogenesis of ME/CFS.

Read the full article: Mozhgani 2022