HHV-6 seronegativity pre-transplantation predicts HHV-6 viremia post-transplantation

HHV-6 reactivation following pediatric liver transplant (LT) patients is variable, ranging from 4-53% (Phan et al 2018.) Furthermore, since many LT procedures are performed before some children have experienced primary infection with HHV-6, and since children scheduled for LT are not routinely tested for HHV-6, it has been unclear whether a previous history of HHV-6 infection affects the likelihood of viremia, liver infection by the virus and frank hepatitis associated with the virus.

Mysore et al. of Baylor College of Medicine examined HHV-6 serologies preceding LT. Of the 96 pediatric LT recipients who had pretransplant HHV-6 serologies, 62 (64.6%) were seropositive and 34 (35.4%) were seronegative for HHV-6.

Post-transplantation, some patients developed HHV-6 viremia, typically with associated fever and elevated liver enzymes (ALT/AST). The HHV-6 infection appeared to respond to antiviral treatments (that were typically being given for presumed CMV infection, not for HHV-6 infection). Interestingly, this occurred more often in the seronegative patients (32%) than in seropositive patients (4%) (P=0.002). This may initially seem counterintuitive, since it was the patients who were seropositive pre-transplantation who harbored HHV-6, and in whom the virus was at increased risk of reactivating due to the immunosuppression of transplantation.

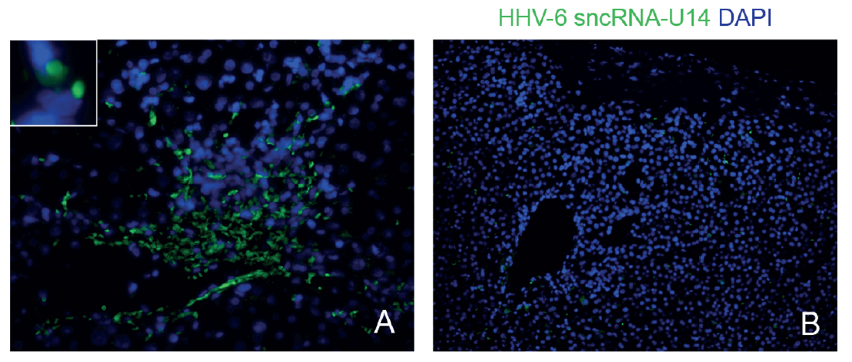

However, HHV-6 was subsequently detected in 92% of allograft liver biopsies, by a sensitive in situ hybridization assay. These biopsies typically were not performed at the time of HHV-6 viremia, but for other reasons. Indeed, at the time of the positive biopsy, HHV-6 viremia was typically absent.

In situ hybridization (ISH) results: (A) Positive human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) ISH. (B) Negative HHV-6 ISH.

Thus, this study strongly suggests that young children who are seronegative for HHV-6 before liver transplantation are at greater risk for developing HHV-6 viremia post-transplantation, and that the source of the virus in many cases probably is the donor liver or the donor leucocytes that accompanied the liver.

Was the virus found in the liver the cause of the hepatitis? Not only viral DNA, but expression of viral RNA was documented, indicating viral replication. It is not clear from the positive in situ hybridization studies that the infected cells were hepatocytes (as contrasted to infiltrating lymphocytes), nor is it clear that the cause of the elevated liver enzymes was a cytolytic effect of the virus, as contrasted to an inflammatory response to the virus. Nevertheless, it is plausible that HHV-6 caused hepatitis in some cases.

This study demonstrates a potential benefit of determining serological status of HHV-6 in children preceding LT. It also underlines the importance of considering HHV-6, as well as CMV, when children undergoing LT develop fever, elevated liver enzymes and other manifestations of viremia and hepatitis.

Read the full article: Mysore 2021