Adeno-associated virus (AAV) linked to Japanese cases, but whether HHV-6 was a cofactor is uncertain.

Not long after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, over 2,000 cases of a severe form of hepatitis in young children were reported from around the world—primarily the U.K. and the U.S. Alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels averaged in the thousands and some children required liver transplantation. The condition was not caused by any of the known hepatitis viruses.

It was tempting to conclude that SARS-CoV-2 might be responsible, since it can infect the liver. Laboratories around the world began a systematic search for multiple possible viruses. As summarized in a previous edition of this newsletter, three studies in Nature reported that the primary causal agent may be adeno-associated virus type 2 (AAV2), a parvovirus that requires the presence of adenoviruses or herpesviruses to become pathogenic (Servellita 2023; Morfopoulou 2023; Ho 2023). HHV-6 was such a possible cofactor in some cases.

The three studies made it highly likely that the combination of three factors lie at the heart of this severe form of viral hepatitis in children: 1) infection with AAV2, possibly a specific and novel strain; 2) coinfection with adenoviruses or possibly with EBV or HHV-6; and 3) having a particular class II HLA allele that increases vulnerability. Little evidence of SARS-CoV-2 serving as a cofactor was found.

These results raised the question of whether similar cases acute hepatitis of unknown cause in children occurred in Japan—both during 2020-2022 and previously. A team from Nagoya University graduate School of Medicine performed a retrospective study of pediatric patients with acute hepatitis from 2017-2023. Control groups included children with acute illnesses (n=50), and children with chronic conditions (n=50) without known liver disease.

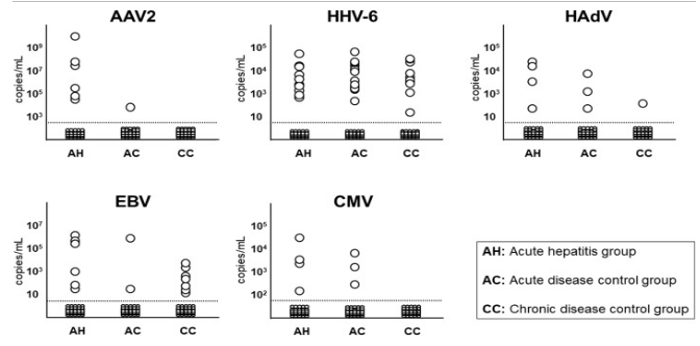

Preserved blood samples were studied using real-time PCR to measure viral loads of AAV2, human adenovirus, HHV-6, EBV and CMV. As shown in the figures below, AAV2 was detected much more often in the acute hepatitis group than in the two control groups. As for the co-factor viruses that might have activated latent AAV2, neither human adenovirus nor EBV, CMV or HHV-6 were clearly established as cofactors (Figure 1).

Figure 1. – Comparison of viral DNA detection rates and viral load of patients with acute hepatitis and the control groups.

Thus, this report finds that AAV2 may have been causing occasional cases of acute hepatitis of unknown cause in children in Japan, and doing so prior to 2020 (when the cases in the U.K. and U.S. were first noted). The viral co-factors responsible for activating latent AAV2, however, were not clearly established.

In 2020-2022, many speculated that SARS-CoV-2 might be a co-factor. Relatively little evidence of that has emerged, although some have argued for an indirect effect: isolation during the pandemic may have prevented children from being exposed to many common viral pathogens, including circulating adenoviruses and adeno-associated viruses, rendering them more vulnerable to these viruses.

Whether previously reported cases of acute hepatitis in children associated with EBV and HHV-6 might also have been found to involve AAV2 had this virus been looked for, is unknown. Whether the AAV2 linked to this illness is a novel strain also remains unproven but possible.

Read the full text: Iwata 2024